Food inflation threatens lives and economic recovery - Financial Times

posted by Lyric Hughes Hale on September 8, 2020 - 12:00am

Shortages are a window on to the challenges facing the post-pandemic world economy. This article originally appeared in the Financial Times.

It’s a sign of the times. In China, teachers are gobbling up the leftovers from their students’ lunch plates, on the spot. Their diligent economising follows an exhortation by President Xi Jinping that the nation needs to reduce food waste, in part to increase Chinese food self-sufficiency.

There are several specific reasons why China is worried about food scarcity: floods and droughts, growing tensions with food exporters such as the US and Australia, and the mass culling of millions of pigs from last year’s outbreak of swine flu, have all taken their toll. In July, Chinese food prices rose by 13 percent year on year.

But it’s not just China where food is a growing concern. Similar worries are playing out globally. In rich and poor countries alike, food shortages are a window on to the challenges of the post-pandemic global economy and the consequences of supply chain disruption and lockdowns.

There is also the risk that rising food prices could presage a general rise in inflation — which in turn could lead to higher interest rates, threatening economic recovery. Just as Covid-19 showed the world was ill-prepared for a global health crisis, we are similarly unprepared for a global food crisis.

The most immediate concern is humanitarian. The UN’s Committee on World Food Security forecasts that malnutrition will double as a direct result of the pandemic, and more people will die of malnutrition and its associated diseases than from coronavirus. The Center for Strategic and International Studies estimates that the number of people globally who face acute food insecurity will nearly double this year to 265m. Oxfam forecasts that 12,000 people could die every day from hunger by the end of the year.

Conflict zones such as Yemen, Syria, Lebanon and North Korea are already experiencing starvation conditions. In Africa, even before the pandemic, around 20 per cent of the population was malnourished. In the Americas, failed states such as Venezuela face worsening hunger and food inflation. Yet the problem is not limited to failed states or developing countries.

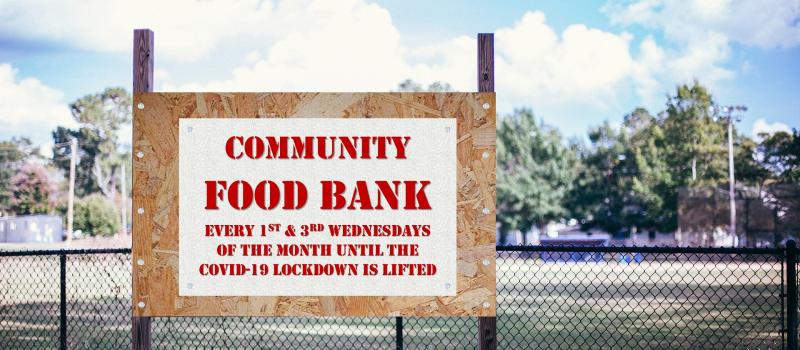

Food insecurity is also rising in nations as rich as the US, where more than one in five households report they do not have enough to eat, food bank lines have grown longer during the pandemic, and school closures have meant that some children who depended on school for a daily meal have missed out. That food costs are rising now might seem counterintuitive in a world where energy prices, a key input in food production, remain low. But US food prices have already risen more than 4 per cent over the past 12 months, despite a 30 per cent fall in oil prices over the same period. And energy prices could also start to climb in the geopolitical blink of an eye.

Rising food prices may also seem counter-intuitive given that record US corn and soya bean crops are forecast this year; some areas of food production such as meat and poultry have adapted relatively well to the Covid-19 shock through automation; and globally, rice and wheat production is robust. Yet food production by itself is not enough.

As Covid-19 spread across the globe, producers such as Russia and Thailand curbed exports. Food importing countries also stockpiled reserves. And some private producers could not distribute the food they did grow: the abrupt end of restaurant eating, for example, meant many farmers could not sell their produce and had to throw it away. All of this distorted prices. It is also a reminder that the problem is less about the quantity of food produced than how it is distributed. As economist Amartya Sen concluded in his seminal study of the 1943 Bengal famine, it was lack of information and poor policies, not food availability, that led to mass starvation.

The link between hunger and political unrest throughout history is obvious. Today, it could lead to a world where there are not only wide differences of income but also, more starkly, between the hungry and the fed.

The potential macroeconomic effect of food shortages are also clear. Rising prices could push up inflation and, in our debt-fuelled world, even a small uptick in interest rates could break economic recovery before it takes hold.

Are there any immediate solutions or easy wins? Information technologies could help create greater efficiencies. Blockchain could even find one of its best uses in tracking food on its journey from farm to table, helping to improve market transparency. Either way, the alternative is grim. If conditions continue to worsen, each nation will fend for itself and a global hunger games could begin, with lethal consequences for the poor and the hoped-for economic recovery.