China’s Relationship with Chile: The Struggle for the Future Regime of the Pacific

posted by R. Evan Ellis on January 18, 2018 - 9:25am

I am sharing with you my article on Chinese engagement with Chile, recently published by the e-journal "China Brief." The article, based on research and interactions during my November 2017 engagement in Santiago is also available at the website of the Jamestown Foundation.

Though superpower diplomacy dominated coverage of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation forum (APEC) leaders summit in November, China’s upgrading of a free-trade agreement with Chile served to highlight the strength of an economic and political relationship that it has built with the country, and the influential position Chile currently occupies in shaping Chinese engagement with Latin America.

The agreement signed at APEC builds on a free-trade agreement first signed in 2005—the first of its kind between a South American nation and China. At first glance, China’s interactions with Chile appears to resemble its pattern of behavior with the region in general. Chile’s exports to the China are dominated by a limited number of low value-added commodities, including copper and potassium nitrate (used as fertilizer). Correspondingly, a broad range of Chinese products have significantly penetrated the Chilean market, from cheap manufactured goods, to motorcycles, cars, cell phones and computers.

On closer examination, China’s relationship with Chile has multiple elements that distinguish it from its relationship with others in Latin America.

Chile has been one of the most successful countries in the region in establishing a national brand in the PRC and positioning its products in the non-commodity goods segment of the Chinese market. Chile last year replaced Vietnam as the principal supplier of fresh fruit imported by the PRC (Santiago Times, April 2). Although the time and expense of shipping products to the PRC creates a barrier for non-differentiated agricultural goods, Chile has successfully positioned its cherries, table grapes, blueberries as luxury goods in China. Chilean wines have achieved similar recognition in the PRC, as consumption by the Chinese middle class grows.

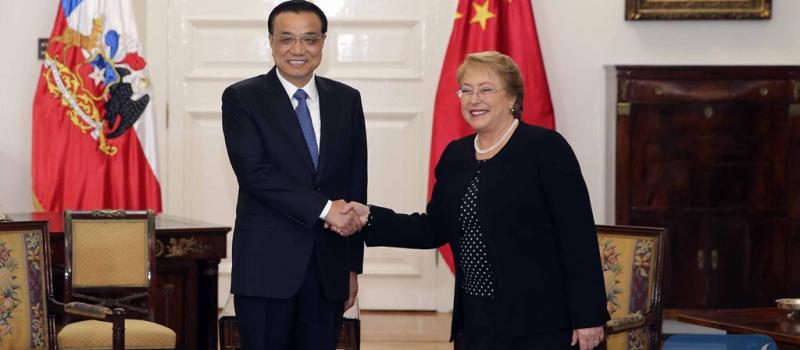

Despite such success, and Chile’s reputation for efficiency, security, and rule of law, investment by Chinese companies in the country ranks among the lowest in the region. The Chilean government has taken note of the contrast between its successes in exporting its products to China, with its inability to attract significant Chinese investment. The annual “Chile Week” program, conducted in six of China’s largest cities since 2015, is an example of attempts by the government of Michelle Bachelet to remedy this deficiency (Santiago Times, August 30).

Ironically, the lack of Chinese direct investment in the country partially reflects Chile’s relatively good governance and strong institutions; Chinese companies often prefer to invest where they can secure state-to-state deals on preferential terms. Chile, with its good access to capital markets has not felt compelled to adapt its laws and regulations, such as those governing public procurement, to attract Chinese loans or investors.

Further inhibiting Chinese investment, Chile’s mining sector, the principal source of the country’s exports to the PRC, is generally off limits to equity investments. While the Chilean state mining entity CODELCO signed a $500 million agreement in 2005 for the advance purchase of Chilean copper, the deal went sour when the Chileans found themselves locked into a long-term agreement to sell almost 5 percent of their copper exports to the PRC at prices substantially below the market price. The Chilean government ultimately forced Minmetals to back out of its option to acquire a 49 percent the Gabriel Mistral (Gaby) mine, which it had used the Chinese loan to develop (Business News Americas, September 29, 2008). Chinese interest in investing in the Chilean mining sector virtually disappeared for years thereafter.

Despite such setbacks, in recent years, Chinese have expressed renewed interest in Chilean mining, focused on lithium, a strategic metal used in modern batteries to power devices from cars to cellphones.

Beginning in 2016, Chinese mining company Tianqi quietly began acquiring a minority share of Chilean lithium producer SQM. In October 2017, the Chinese petrochemicals giant Sinochem made public an intention to acquire a majority stake in SQM for $4.5 billion from the Canadian firm Potash (La Tercera, October 23, 2017). The Chilean government is currently evaluating bids for “value-added” development of its lithium reserves, in which four of the 12 companies bidding are Chinese. Each bidder must propose a project for how it will provide value added to the lithium within Chile. One contender is the Chinese MTL-Shenzen group, who, with a Korean partner, is proposing a project to build a factory to build lithium-ion batteries in the area where it will extract the metal (La Tercera, July 7). As China attempts to position itself as a leader in battery technology and production, these investments in strategic materials will be key to keeping Chinese batteries cheap and globally competitive.

In the telecommunications sector, as in other parts of Latin America, the Chinese company Huawei has established itself as an important player in the mobile telephone market, to include commercial facilities, and presence as a local brand, including the recruitment of one of Chile’s best-known soccer players as the face of the company in its Chilean advertising. Huawei has also won a contract for one of three tranches of a project to construct a submarine fiber-optic cable connecting the south of Chile from Puerto Montt to Puerto Williams, which may be a stepping stone for a Huawei role in an even more ambitious cable connecting China to South America through Chile (Ministerio de Transportes y Telecomunicaciones, October 16, 2017).

In the space sector, the PRC is building an observatory approximately 30 miles from the facility that it already shares with Chile’s Catholic University, in Paranal, in the Atacama Desert (La Tercera, 2016). Although in 2008, the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) lost a bid to participate in the Chilean FASAT-C satellite program to the European firm Astrium, as the satellite neared the end of its useful life, Chile’s ambassador to the PRC Jorge Heine suggested that his country might turn to China’s Beidou satellite to replace it (Xinhua, April 27, 2016).

With respect to the electricity sector, one of the largest investments by a PRC-based company in Chile was that of Sky Solar, which committed to invest more than $1.3 billion to construct farms of photovoltaic cells to generate solar energy in the Atacama Desert (El Mercurio, January 25, 2013). Chinese companies have also been involved in a series of projects for wind generation (Global Wind Energy Council).

Despite such advances, and although power generation and transmission in Chile is in the hands of the private sector with a relatively modest regulatory burden, Chinese companies have not yet entered the sector in force, as Chinese companies such as State Grid, Three Gorges and State Power Industrial Corporation (SPIC) have entered Brazil (Newsmax, October 9, 2017). Nonetheless, that may be changing with SPICs acquisition of Pacific Hydro, which gives the company control over five hydroelectric facilities in Chile (Hydroworld, December 17, 2015).

Chile’s stable and developed financial system and access to international capital markets has limited the need for loans from Chinese policy banks such as China Development Bank and China Export-Import bank, often tied to the use of Chinese companies and laborers in the projects financed. Yet the same strength and sophistication of Chile’s financial system has also allowed the country to become the regional hub for clearing transactions conducted in Chinese RNB. To this end, the two countries have invested $189 million to establish a clearing bank in Chile, tied to China Construction Bank, as well a $3.5 billion currency swap agreement between the central bank of Chile and the People’s Bank of China (Xinhua, June 21, 2016). Chile, for its part, was one of the first Latin American companies to join the PRC-sponsored Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), in May 2017 (Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, May 13).

Beyond traditional industries, tourist visits by PRC nationals to Chile are also on the rise. In 2016, almost 23,000 Chinese visited Chile, a 49 percent increase over the previous year, while in the first four months of 2017 almost 11,000 Chinese tourists visited, representing a further 51 percent year-on-year increase (Lun, July 2).

The Chinese ethnic community in Chile reportedly plays an important role in the expansion of such tourism. Although the community is relatively small, with an estimated 30,000 persons, many are recent arrivals who have acquired legal Chilean residency, yet have retained fluency in Mandarin Chinese or Cantonese and connections in the PRC. These Chinese Chileans who reportedly play a key role in bringing tour groups to Chile from the mainland, and coordinating with Chinese restaurants and Mandarin-speaking service providers in Chile to provide a culturally comfortable experience in Chile for visiting Chinese. One Chilean tour group operator indicated to the author that 70 percent of his business is now with the Chinese, although he had done almost no business with them a few years earlier.

Chinese activities in Chile’s defense sector have been minimal. Nonetheless, in June 2015, Chile’s Minister of Defense Jose Antonio Gomez traveled to the PRC to meet with his Chinese counterpart, Chang Wanquan to boost defense cooperation (Xinhua, June 24, 2015). A modest number of Chilean officers regularly travel to China for professional military education programs, and Chinese arms companies also had a significant presence at the Exponaval trade show in Santiago (Exponaval 2016).

In the end, Chile’s relationship with China will be critical in shaping the dynamics of the China relationship with Latin America in general. As noted previously, Chile’ success in placing products in the PRC has made its practices an important reference for the rest of the region. Reciprocally, its insistence on not bending Chilean laws and contracting procedures to accommodate Chinese companies, as occurred in many other countries across the region, provides an important indication of whether it is possible to attract Chinese investment and maintain a healthy business relationship within the framework of a nation’s existing laws and regulations.

Chile’s orientation toward China will also be important at the regional level. In the wake of the U.S. withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the support of Chile will be instrumental in taking forward a new version of the deal, denoted as “TPP 2”, which would make an important contribution in defining a Trans-Pacific commercial regime which addresses non-tariff barriers to trade, and which protects the intellectual property of the participating nations far more than the alternative “Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific” currently being promoted by China (Xinhua, November 3). U.S. policymakers should take note of what is happening in Chile, which has long been a friend to the United States, and where U.S. political and economic ideals have long found common ground.

The United States continues to have many friends in the region, yet the deepening of Chile’s relationship with the PRC is generating subtle yet significant changes in attitudes, not only about U.S. policy and requests, but also how Chileans react to parts of the U.S. style that they may find distasteful. Chinese activities in Chile, met with traditional Chilean warmth and efficiency, are an important wake-up call to take greater stock of how engagement with the PRC is transforming the region in ways that are increasingly uncomfortable for the United States, its global position, and the pursuit of its policy agenda.